G2P Part 4: advanced mappings with g2p

This is the 4th blog post in a seven-part series about g2p. This is a relatively long post, where we get in to all the nitty gritty of writing complex mappings in g2p.

G2P Blog Series Index

- Background

- How to write a basic mapping in G2P Studio

- Writing mappings on your computer

- Advanced mappings

- ReadAlong Studio & Other Applications

- Preprocessing mappings

- Contributing

NOTE!

As of September 2023, there is a new version of g2p available: 2.0 - the instructions in this blog were originally written for version 1.x. If you already have g2p installed, we recommend that you upgrade your installation before continuing on with this post.

Advanced: A deeper dive into writing tricky rules

You may have noticed that the rules described in the previous posts for converting words like ‘dog’ and ‘cat’ to IPA are woefully incomplete. The real world use cases for g2p often need to account for a lot more messiness than was described in the artificial example above. In fact, for languages like English, g2p is likely not a good solution. The English writing system is notoriously inconsistent, and there already exist a variety of other tools that account for many of the lexical (word-specific) idiosyncracies in deriving the IPA form from the orthographic form. For many Indigenous languages, the writing system is sufficiently close to the spoken form that g2p is a very appropriate solution. In the following sections, I’ll describe some common problems when writing rules, and how to fix them.

As this post is quite long, please refer to the following index for quick navigation:

- Rule Ordering

- Unicode Escape Sequences

- Special Settings & Configuration

- Defining variables

- Regular Expresssions

- Using indices

Rule Ordering

The order of your rules in g2p really matters! This is because some rules can either create or remove the context for other rules to apply. In linguistics, these rule ordering patterns are usually talked about as either feeding, bleeding, counter-feeding, or counter-bleeding relationships. There are potentially valid reasons to want to encode any of these types of relationships in your rules.

To illustrate a possible problem, let’s consider a g2p mapping for language that converts ‘a̱’ to ‘ə’ and ‘a’ to ‘æ’. ‘a̱’ is a sequence of a regular ‘a’ followed by a combining macron below (\u0331). Because \u0331 (‘a̱’) is easily confusable with \u0332 (‘a̲’), in order to follow the rule of thumb for Unicode escape sequences, I’ll write the rules as follows:

| in | out |

|---|---|

| a | æ |

| a\u0331 | ə |

Now, assuming an input to this mapping of ‘a̱’ (a\u0331), we would get ‘æ̱’ (æ\u0331) instead of ‘ə’. Why is that? Because the first rule applies and turns ‘a’ into ‘æ’ before the second rule has a chance to apply. This is called a bleeding relationship because the first rule bleeds the context of the second rule from applying. In order to avoid it, we would need to write our rules as follows:

| in | out |

|---|---|

| a\u0331 | ə |

| a | æ |

With this ordering, our input of ‘a̱’ (a\u0331) would turn into ‘ə’ as we expect, and our input of ‘a’ would turn into æ also as expected. Try it out on the G2P Studio if you don’t believe me!

Unicode Escape Sequences

Sometimes you need rules to convert from characters that either don’t render very well, or render in a confusing way. In those cases, you can use Unicode escape sequences. For example, maybe you want to write a rule that converts the standard ASCII ‘g’ to the strict IPA Unicode /ɡ/. As you can likely see in your browser, these characters look very similar, but they’re not the same character! The ASCII ‘g’ is U+0067 and the strict IPA ‘ɡ’ is U+0261. So, you can write a rule as follows:

| in | out |

|---|---|

| \u0067 | \u0261 |

or using JSON:

[

{

"in": "\u0067",

"out": "\u0261"

}

]

This is also helpful when you need to write rules between combining characters or other confusable characters. The rule of thumb is, if your rules are clearer using Unicode escape sequences, do it! Otherwise, just use the normal character in place.

Tip for finding a character’s codepoint

If you want to find out what a particular character’s \uXXXX notation is, simply paste the character(s) into the search bar of this handy site: https://unicode.scarfboy.com/ and you will get a list of the Unicode codepoints for those characters.

Note, you might find some resources that write a character’s codepoint as U+0261 instead of \u0261. The U+XXXX format is the one officially adopted by the Unicode consortium, as early as of Unicode 2.0.0. However, the Python programming language uses the \uXXXX format. The important part is recognizing that the Unicode codepoint is identified by the XXXX hexadecimal sequence.

Special settings for your mapping configuration

You can add extra settings to your configuration file to change the way that g2p interprets your mappings. Below is a list of possible settings and their use. It’s best practise to declare all the setting keys below for each individual mapping in your config-g2p.yaml, however default values do exist. Your setting keys must be declared on the same level as all of the other keys (language_name, in_lang, out_lang etc). These settings are also available in the G2P Studio as check boxes to select or unselect.

rule_ordering (default: ‘as-written’)

As described in the earlier part of this post, your rules apply in the order you write them. And as described in the advanced section on rule ordering, sometimes this can make your mapping produce unexpected results!

If you set your mapping to rule_ordering: 'apply-longest-first', g2p will sort all of your rules based on the length of the input to the rule, so that rules with longer inputs apply before rules with shorter inputs. This prevents some common ‘bleeding’ rule-ordering relationships described in the rule ordering section. So, if you declared your rules as:

[

{

"in": "a",

"out": "b"

},

{

"in": "ab",

"out": "c"

}

]

Then, with rule_ordering: 'as-written' (the default), you would get ‘bb’ as the output for the input ‘ab’. Whereas with rule_ordering: 'apply-longest-first', you would get ‘c’ as the output for the input ‘ab’.

mappings:

- language_name: English

display_name: English to IPA

in_lang: eng

out_lang: eng-ipa

type: mapping

authors:

- Aidan Pine

rules_path: eng_to_ipa.json

rule_ordering: 'apply-longest-first' # <------- Add this

case_sensitive (default: true)

The default is to treat your rules as case sensitive, but setting case_sensitive: false, will make your rules case insensitive.

mappings:

- language_name: English

display_name: English to IPA

in_lang: eng

out_lang: eng-ipa

type: mapping

authors:

- Aidan Pine

rules_path: eng_to_ipa.json

case_sensitive: false # <------- Add this

escape_special (default: false)

As I will describe later in the section on regular expressions, you can define rules using ‘special’ characters. By default, these characters are interpreted as ‘special’, but if you want all special characters in your mapping to be interpreted as their actual characters, you can set escape_special: true.

mappings:

- language_name: English

display_name: English to IPA

in_lang: eng

out_lang: eng-ipa

type: mapping

authors:

- Aidan Pine

rules_path: eng_to_ipa.json

escape_special: true # <------- Add this

norm_form (default: “NFD”)

If you’ve never heard of Unicode normalization don’t worry, you’re not alone! But, for writing rules and mappings using g2p, there can be some surprising ‘gotcha’ moments if you don’t choose the right normalization strategy.

The basic gist of the problem is that there can be multiple ways to write the same character in Unicode, depending on whether you use ‘combining characters’ to type or not. For example, on some keyboards, you might type ‘é’ by writing an e first and then another keystroke to type the acute accent that sits above it. The Unicode representation for this would be \u0065 (e) followed by \u0301 (a combining acute accent), however there is an entirely separate Unicode code point that has these two characters pre-composed (\u00e9), which some keyboard layouts will generate instead.

Many fonts will render these two different representations identically and it can be really difficult and confounding as a user if both appear in the same text. This causes problems, like text that looks identical will not appear in “find & replace” or search engines will not find the text that you’re looking for, even though something that looks identical exists. Luckily, there is a standard for normalizing these differences so that all instances of sequences like \u0065\u0301 would be (NF)Composed into \u00e9, or the opposite direction where all instances of \u00e9 would be (NF)Decomposed into \u0065\u0301. For a more in-depth conversation on this, check out this blog article.

mappings:

- language_name: English

display_name: English to IPA

in_lang: eng

out_lang: eng-ipa

type: mapping

authors:

- Aidan Pine

rules_path: eng_to_ipa.json

norm_form: "NFC" # <------- Add your Unicode normalization strategy here

out_delimiter (default: ‘’)

Some mappings require that a delimiting character (or delimiting characters) be inserted whenever a rule applies. So, using the example from the first part of this post, maybe you want kæt to go to kʰ|æ|t instead of kʰæt. For this, you would set out_delimiter: "|" in your mapping.

mappings:

- language_name: English

display_name: English to IPA

in_lang: eng

out_lang: eng-ipa

type: mapping

authors:

- Aidan Pine

rules_path: eng_to_ipa.json

out_delimiter: "|" # <------- Add your delimiter here

reverse (default: false)

Setting reverse: true will try to reverse the mappings so that all characters defined as out in your mapping become the input characters and vice versa. Except for a few cases, this is unlikely to work very well for advanced mapings.

mappings:

- language_name: English

display_name: English to IPA

in_lang: eng

out_lang: eng-ipa

type: mapping

authors:

- Aidan Pine

rules_path: eng_to_ipa.json

reverse: true # <------- Add this

prevent_feeding (default: false)

Let’s say you have the following rules:

| in | out |

|---|---|

| kw | kʷ |

| k | kʲ |

Let’s say the intended output here is that whenever we get a kw as an input, we get kʷ and whenever we get k we get kʲ. Ordered in the way they are defined, an input of kw will produce kʲʷ and ordered the other way, an input of kw will produce kʲw. Neither of these are correct though! So, how do we solve this? There is a setting called prevent_feeding which, if set to true, will prevent the output of one rule from being processed by any subsequent rule. As described in the rule ordering section the process when one rule provides the context for another rule to apply is called ‘feeding’. And so this setting is named prevent_feeding because it prevents that from happening. Note, setting prevent_feeding: true for your whole mapping will do this for every rule. If you just want to prevent feeding for one particular rule, you can write your rules in JSON and add the key to the specific rule you want to prevent feeding for.

Prevent feeding for a single rule (in JSON rule mapping file):

[

{

"in": "kw",

"out": "kʷ",

"prevent_feeding": true

},

{

"in": "k",

"out": "kʲ"

}

]

Prevent feeding for every rule (in config-g2p.yaml):

mappings:

- language_name: English

display_name: English to IPA

in_lang: eng

out_lang: eng-ipa

type: mapping

authors:

- Aidan Pine

rules_path: eng_to_ipa.json

prevent_feeding: true # <------- Add this

Defining sets of characters

Some rules are written with repeating sets of characters that can be tedious to write out. As a result, we might want to define certain sets of reusable characters using a variable name. These can be written using special types of mapping files in g2p.

For example, consider a series of rules which contextually apply only between vowels. Let’s say as an example of one of those rules, that dd turns to ð when it exists between two vowels. This language has the following vowels in its inventory: a,e,i,o,u,æ,å,ø. You could write the rules like this1:

| in | out | context_before | context_after |

|---|---|---|---|

| dd | ð | (a|e|i|o|u|æ|å|ø) | (a|e|i|o|u|æ|å|ø) |

But, if there are lots of rules with these vowels, this could get very tedious, not to mention annoying and error-prone if the characters in the set change at some point. It is also less readable, and leaves the reader of the mapping to infer the meaning of the rule.

So, in a separate file, by convention it is usually called abbreviations.csv, you can define a list of sets where each row is a new set. The first column contains the name of the set (by convention this is capitalized), and you can add characters to every following column. So, for example:

| variable name | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VOWEL | a | e | i | o | u | æ | å | ø | |||||||

| CONSONANT | p | b | t | d | k | g | f | s | h | v | j | r | l | m | n |

| FRONT | i | e | œ | ø | y | ||||||||||

| BACK | u | o | a |

Then, in your configuration, you can add the file to a specific mapping using abbreviations_path: abbreviations.csv. After adding it to your mapping, you can write the above rule like this instead:

| in | out | context_before | context_after |

|---|---|---|---|

| dd | ð | VOWEL | VOWEL |

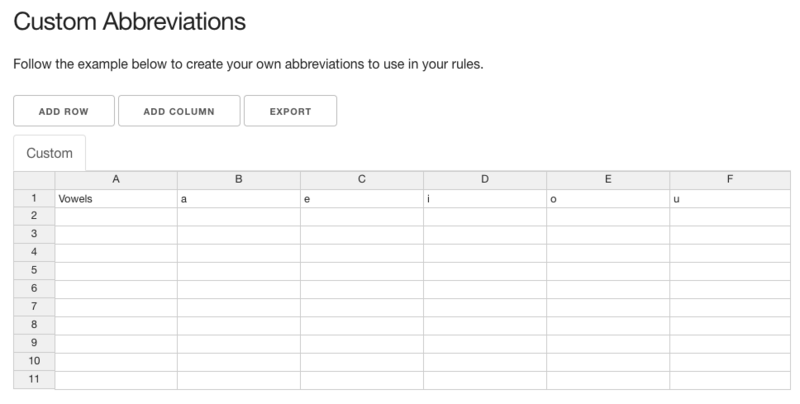

You can also use abbreviations like this in the G2P studio by writing them in the section at the bottom of the page titled ‘Custom Abbreviations’ They will be automatically applied to your custom rules above.

Regular Expressions

Regular expressions are used ubiquitously in programming to define certain search patterns in text. In fact, this is how g2p rules work! They eventually get compiled into a regular expression too. For the most part, you can add regular expression syntax to your rules. So, suppose you wanted to write a rule that deleted word-final ‘s’, you could write the following:

| in | out | context_before | context_after |

|---|---|---|---|

| s | \B | \b |

As you can see in this handy regular expression cheatsheet our rule turns ‘s’ into nothing if it is preceded by \B (any character that is not a word boundary) and followed by \b (word boundary).

Note: There are some ‘gotchas’ with writing regular expressions using g2p. This is a technical note, but if you’re writing some complicated regular expressions and they’re not working, don’t hesitate to raise an issue. For example there are some active issues around edge cases where regular expressions and g2p’s custom syntax for indices don’t play nice together.

Using specific indices

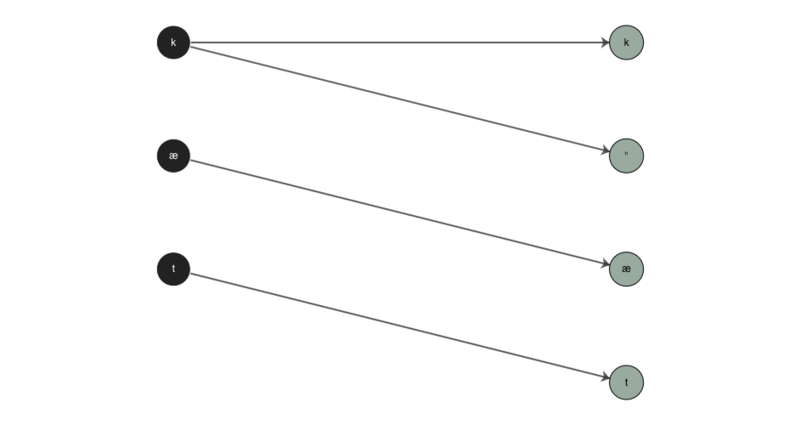

Even people familiar with using g2p might not be aware that one of its main features is that it preserves indices between input and output segments. Meaning that when we convert from something like ‘kæt’ to ‘kʰæt’ as in the first example, g2p knows that it’s the ‘k’ that turned into the ‘k’ and ‘ʰ’ as seen below.

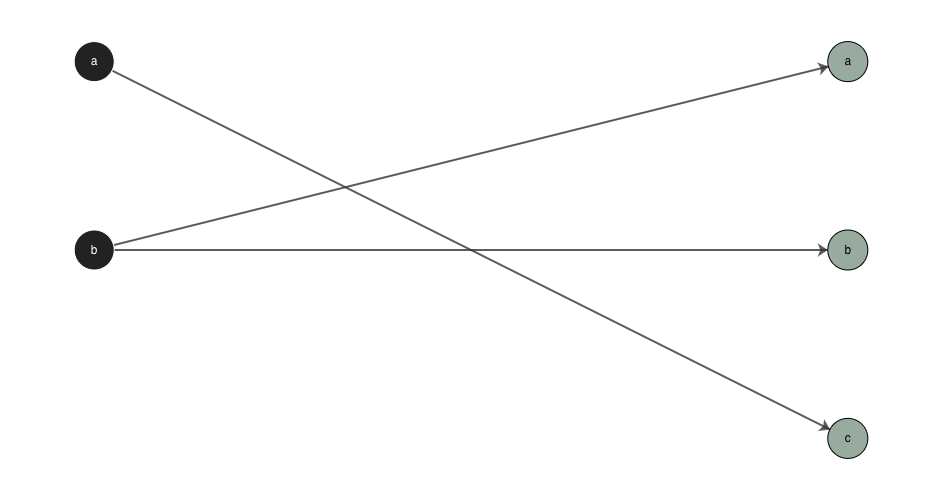

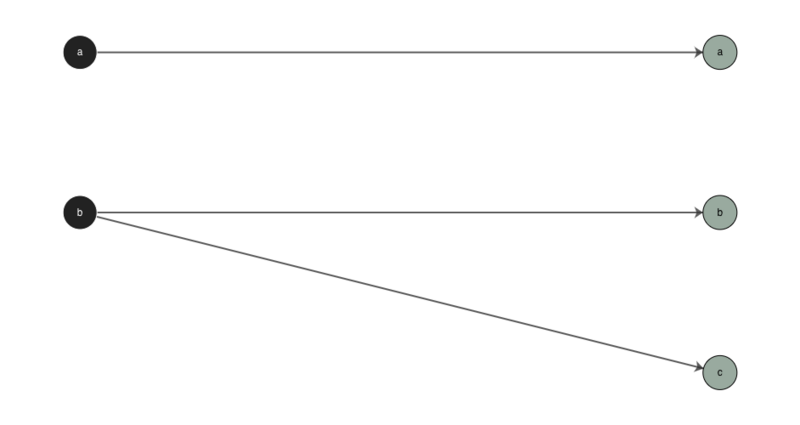

The default interpretation of rule indices by g2p is that it matches the characters between the input and the output one-by-one in a given rule until it reaches the end of either one, then it matches any remaining characters in the longer part (input or output) to the last character of the shorter part. For example, compare the following examples where ‘abc’ is converted to ‘ab’ and gloms the excess input character onto the last output character:

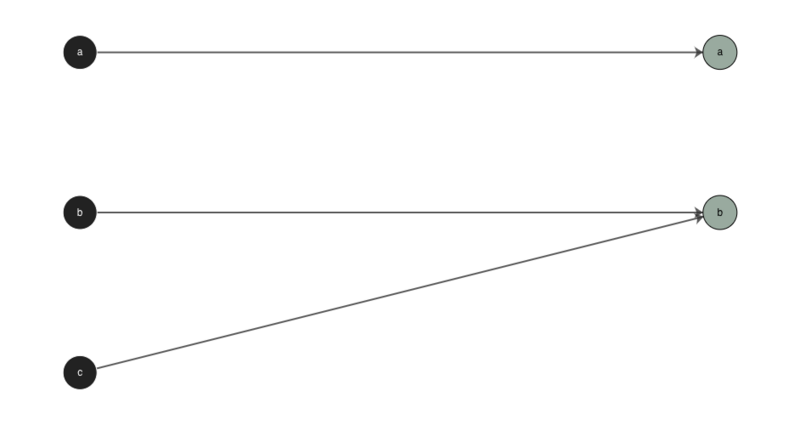

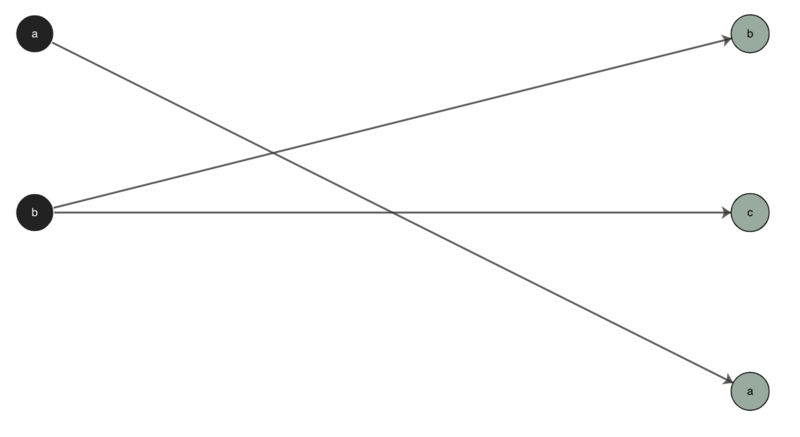

and where ‘ab’ is converted to ‘abc’ and gloms the excess output character onto the last input character:

But what if - for some imaginary reason - we want to show a rule where ‘ab’ turns into ‘bca’, and specifically make note that it was ‘b’ that turned into ‘bc’, and ‘a’ stays as ‘a’? Well, we can use special g2p syntax for explicitly writing these indices. Instead of,

| in | out | context_before | context_after |

|---|---|---|---|

| ab | bca |

we can write

| in | out | context_before | context_after |

|---|---|---|---|

| a{1}b{2} | bc{2}a{1} |

Now, our indices will reflect our imaginary need to index ‘a’ with ‘a’ and ‘b’ with ‘bc’:

Using the explicit indices syntax will break up your rule into a number of smaller rules that apply the same defaults of above but to explicit sets of characters. You must use curly brackets, but the choice of character you put inside is arbitrary — it just has to match on both sides. By convention, we use natural numbers. This will match all the characters to the left of each pair of curly brackets in the input with the matching index in the output. So here, ‘a’ is matched with ‘a’ and ‘b’ is matched with ‘bc’.

These can get fairly complicated, so we recommend only using this functionality either for demonstration purposes, or for specific applications which require the preservation of indices.

Writing Mappings in Python

You can also write mappings directly in Python like so:

from g2p.mappings import Mapping, Rule

from g2p.transducer import Transducer

mapping = Mapping(rules=[

Rule(rule_input="a", rule_output="b", context_before="c", context_after="d"),

Rule(rule_input="a", rule_output="e")

])

transducer = Transducer(mapping)

transducer('cad') # returns "cbd"

You can write your rules directly in your yaml files

So instead of using a rules_path key, you can just use rules instead:

mappings:

- language_name: My Test Language # this is a shared value for all the mappings in this configuration

display_name: My Test Language to IPA # this is a 'display name'. It is a user-friendly name for your mapping.

in_lang: test # This is the code for your language input. By convention in g2p this should contain your language's ISO 639-3 code

out_lang: test-ipa # This is the code for the output of your mapping. In g2p we suffix -ipa to the in_lang for mappings between an orthography and IPA

type: mapping

authors: # This is a way to keep track of who has contributed to the mapping

- Aidan Pine

rules:

- in: a

out: b

- in: c

out: d

prevent_feeding: True

Footnotes

-

You’ll notice that the syntax here is a little weird, what the heck are all of those pipes (the up-down things like |) doing there? That’s because I’m using regular expressions to express a OR e OR u etc… For more info, check out the section on regular expressions ↩

Never miss a

story from us, subscribe to our newsletter

Never miss a

story from us, subscribe to our newsletter